|

Abstract

Background and Objective: Acquired dermal melanocytosis (ADM;

acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules) is known for

its recalcitrance compared to Nevus of Ota, and one of the

reasons seems to be a high rate of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

(PIH) after laser treatments.

Methods: Topical bleaching treatment with 0.1% tretinoin

aqueous gel and hydroquinone ointment (4-6 weeks) was initially

performed to discharge epidermal melanin. Subsequently, Q-switched

ruby (QSR) laser was irradiated to eliminate dermal pigmentation.

The both steps were repeated until patients' satisfaction

was obtained. This treatment was performed in 19 patients

with ADM. Skin biopsy was performed in 6 cases at baseline,

after the bleaching pretreatment, and at the end of treatment.

Results: All patients showed good to excellent clearing after

2 to 3 sessions of QSR laser treatments. Total treatment

period ranged from 3 to 13 (mean = 8.3) months. PIH was observed

in 10.5 % of the cases. Histologically, epidermal hyperpigmentation

was observed in all specimens, and was dramatically improved

by the topical bleaching pretreatment.

Conclusion: QSR laser combined with the topical bleaching

pretreatment appeared to consistently treat ADM with low

occurrence rate of PIH and lessen the number of laser sessions

and total treatment period, and may also be applied to any

other lesions with both epidermal and dermal pigmentation.

Introduction

Nevus of Ota, first described by Ota and Tanino as nevus

fuscocaeruleus ophthalmo-maxillaris in 19391, is usually

unilaterally located in the area innervated by the ophthalmic

and maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve. A typical nevus

of Ota is a flat blue-black or slate-gray macule intermingled

with small, flat, and brown spots. Pigmented macules are

also often present in ocular, oral, and nasal mucous membrane.

On the other hand, acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules

(Hori's nevus) is an acquired pigmented lesion involving

bilateral grayish-brown facial macules that was first reported

by Hori et al. in 19842. This condition and its similar conditions

have been referred to as acquired dermal melanocytosis (ADM)

by some Japanese dermatologists3,4, and we call this condition "ADM" in

this article. ADM onsets later in life most after 20 years

of age, represents bilateral involvements, with the malar

regions almost always affected; and a lack of mucosal and

optic involvement2. It is rare in Caucasians but relatively

common in Asian females, and is seen much more frequently

than nevus of Ota 5. There is a report that it occupied 7.5

% of cosmetic skin complaints in Japan6. Clinically, it can

be easily distinguished from nevus of Ota by bilateral presentation,

spot distribution, and difference in color, whereas, in some

atypical cases, it can be rarely misdiagnosed as melasma.

There are two significant differences in histology between

nevus of Ota and ADM; 1) melanocytes are diffusely distributed

throughout the entire dermis in nevus of Ota, while they

are located only in the upper dermis in ADM, and 2) epidermal

hyperpigmentation is not seen in nevus of Ota, while it is

always prominent in ADM; the latter was not well documented

before, but confirmed in a series of our samples. Difference

in color between nevus of Ota and ADM is due to these histological

differences. Although nevus of Ota responds Q-switched lasers

very well7-11, ADM is known for its recalcitrance to conventional

treatments12-15, and one of the reasons seems to be a high

rate of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) seen after

laser treatments12-14. The authors assumed that it was mainly

due to the presence of epidermal hyperpigmentation and property

of epidermal melanocytes in ADM.

The authors previously described an aggressive and optimal

use of tretinoin along with hydroquinone for various kinds

of skin hyperpigmentation15-17. This topical bleaching treatment

was very effective for removal of epidermal pigmentation.

Therefore, we tried the bleaching pretreatment before Q-switched

ruby (QSR) laser for ADM in order to eliminate epidermal

hyperpigmentation and decrease the risk of PIH after QSR

laser treatment. This combination therapy was applied for

patients with ADM, and its efficacy and usefulness was evaluated.

Patients and Methods

Preparation of Ointments: Tretinoin aqueous gels (tretinoin

gel) at 3 different concentrations (0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 %)

were originally prepared at the Department of Pharmacy, University

of Tokyo, Graduate School of Medicine. The precise regimen

of tretinoin aqueous gel was described before16. An ointment

including 5% hydroquinone and 7% lactic acid (HQ-LA ointment),

and an ointment including 5% hydroquinone and 7% ascorbic

acid (HQ-AA ointment) were also prepared. Plastibase (petrolatum

polyethylene ointment base, Taisho Pharmacology, Osaka, Japan)

was used as the ointment base of the HQ-LA ointment, while

the hydrophilic ointment was used for the HQ-AA ointments.

Because tretinoin gel, HQ-LA, and HQ-AA ointments (especially

tretinoin gel) are pharmacologically unstable, fresh ointments

were prepared at least once a month and stored in a dark

and cool (4oC) place.

Evaluations of results:

Photographs were taken for every patient at baseline and

after treatment with a high-resolution digital camera (Canon

EOS-D30). The percentage of pigmentary clearance was evaluated

via the photographs by two experienced plastic surgeons who

did not perform this treatment. The mean data of the pigmentary

clearance of each patient were classified into 4 categories: "excellent" (80%

or more clearance), "good" (50% to less than 80%

clearance), "fair" (0% to less than 50% clearance),

and "poor" (no change or worse).

Patients: Nineteen Japanese patients with ADM were treated

with our treatment protocol. All patients were women. Patient

age at the start of the treatment ranged from 24 to 50 years

old (37.9 ±8.7; mean ± S.D.). The age of onset of ADM was

15-40 years old (24.7 ±7.5; mean S.D.). Pigmented lesions

were located bilaterally on the malar area in all 19 cases

(100%), on the nose in 4 cases (21%), temporal area in two

cases (11%), and forehead in one case (5%). The follow-up

time after the final laser session ranged from 3 to 13 months

(8.3 ±3.7; mean S.D.).

Treatment Methods: Our treatment was composed of two steps.

The first step was a topical bleaching treatment using tretinoin

gel and hydroquinone ointment (6-8 weeks) and the second

step was QSR laser irradiation. The both steps were repeated

until patients' satisfaction was obtained.

1) Topical bleaching treatment: The purpose of this treatment

is to improve epidermal pigmentation by accelerating discharge

of epidermal melanin (by tretinoin) and suppressing new epidermal

melanogenesis (by hydroquinone). The two-phased (bleaching

and healing) treatment was performed as following.

a) Bleaching phase: 0.1 % tretinoin gel and HQ-LA ointment

were applied initially to the skin lesions twice a day. Tretinoin

gel was carefully applied only on pigmented spots using a

small cotton-tip applicator, while HQ-LA ointment was widely

applied with fingers (e.g. all over the face). The way of

ointment application is critical in this aggressive treatment

in order to obtain maximal bleaching effects with minimal

irritant dermatitis. In case in which severe irritant dermatitis

was induced by HQ-LA ointment, HQ-AA ointment was used instead.

Patients were requested to visit our hospital at 1, 2, 4,

6 and 8 weeks after starting this treatment, and every 4

weeks afterwards. When the appropriate skin reaction (that

is, mild erythema and scaling) was not observed at 1 week,

the concentration of tretinoin was changed to 0.4%. In most

cases, it took 4 to 6 weeks to finish this phase.

b) Healing phase: After 4-6 weeks' bleaching phase, the application

of tretinoin gel and HQ-LA ointment was discontinued, and

application of HQ-AA ointment was used in order to prevent

post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) until the redness

was sufficiently reduced. It usually took 2-4 weeks to complete

this phase. Topical corticosteroids were not employed in

either the bleaching or healing phase.

2) QSR laser treatment: In all patients, topical anesthesia

(lidocaine patch; PenlesR, Wyeth Lederle Japan Inc., Tokyo,

Japan) was applied 60-120 minutes before the laser treatment.

For QSR 694.5 nm laser (Model IB101, Niic Co. LTD, Tokyo,

Japan) treatment, spot size of 5 mm, 1 Hz repeat rate, pulse

duration of 20 ns, and fluences ranged from 4.0 to 5.0 J/m2

were used. After laser treatment, topical antibiotics ointment

was applied twice a day until a scale or crust disappeared

(usually for 5-7 days). At 2 weeks after laser treatment,

application of HQ-AA ointment was started.

At 4 weeks after each laser treatment, the topical bleaching

treatment with 0.1% tretinoin gel and HQ-AA ointment was

started as a pretreatment of the next laser irradiation,

and also as a treatment of post-laser PIH in some cases.

In most cases, the bleaching phase for 2 weeks was long enough,

and we can usually estimate the clinical result at 8 weeks

after each laser treatment. When some hyperpigmentation remained,

we can go for the next session. An example of typical time

course was demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Skin biopsy of pigmented regions with a diameter of 2 mm

was performed in 6 cases at baseline, just after the 1st

bleaching treatment, and at the end of the treatment. Sections

were stained with Fontana-Masson staining for visualization

of melanin granules.

Results

Clinical results: In the topical bleaching treatment, erythema

was usually seen in a few days, followed by continual scaling

during the first week. Erythema and scaling were usually

seen continually throughout the bleaching phase. On the other

hand, erythema gradually declined with time in the healing

phase. The difference in color of the macules was usually

observed between before and after the first topical bleaching

treatment; for example, a color change from brown to gray-brown,

or from gray-brown to bluish black, suggesting clearance

of epidermal pigmentation.

All patients showed "good" to "excellent" clearing

after 2 or 3 laser treatments without any complications such

as scarring and persistent depigmentation. Fifteen of 19

cases were evaluated as "excellent" and the other

4 cases as "good" (Table 1). No cases were regarded

as "fine" or "poor". QSR laser treatments

were performed twice in 7 of 19 cases, and 3 times in the

other 12 cases (Table 2). Although PIH apparently occurred

in 2 of 19 cases (10.5 %) after the 1st laser treatment,

PIH was not clearly seen in any cases after the second and

third laser treatments. The average treatment period was

24.8 ± 3.6 (mean ± S.D.) weeks, and the average number of

QSR laser treatment was 2.63 ± 0.5 (mean ± S.D.) times. Although

patients had unpleasing irritant dermatitis during the topical

bleaching treatment, all achieved sufficient satisfaction

with the final results and they were followed up for 8.3

± 3.7 (mean ± S.D.) months (3-13 months) without any evidence

of recurrence. The representative 4 cases are shown in Figs.

2-4.

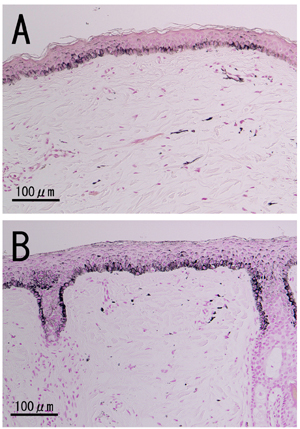

Histological results: At baseline, not only dermal melanocytosis

but also epidermal melanosis around basal layers was seen

in all 6 samples (Fig. 5). In the upper dermis, elongated,

slender, and pigment-bearing melanocytic cells dispersed

between the collagen fibers were observed. In addition, all

6 specimens showed disappearance of rete ridges. In most

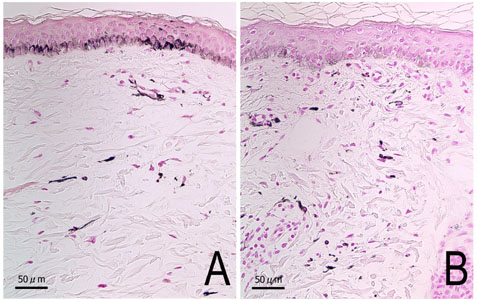

cases, epidermal melanin granules were significantly cleared

after the initial bleaching treatment, while dermal pigmentation

appeared not to change at all (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The first-reported treatment of ADM was cryotherapy19, but

it showed an unpredictable result with a high risk of permanent

scarring and hypopigmentation. Kunachak et al.20 treated

ADM using dermabrasion with successful results. Despite its

advantage as a single session procedure, this approach is

perceived by some patients as an invasive procedure21. Therefore,

QS lasers are considered to be main treatments of ADM today

as well as nevus of Ota.

Although previous reports of QS laser treatments showed good

clearance of ADM12-15,21, it has been pointed out that PIH

and hypopigmentation are frequently observed after the laser

treatments. In ADM, it is known that PIH occurs 2-4 weeks

after laser irradiation in higher degrees and frequency than

in nevus of Ota. Kunachak et al.21 employed repetitive treatment

sessions at only 1-2 weeks intervals. They performed the

second laser session before PIH appeared and reported successful

clearance of ADM but relatively high (5.7 %) risk of hypopigmentation.

Polnikorn et al.12 and Kunachak et al. 14, both used QS Nd:YAG

laser to treat ADM, and reported that the rate of PIH was

71 % and 50 %, respectively. Polnikorn et al.12 waited for

disappearance of PIH before the next session of laser treatment,

and that was 3-6 months. Lam et al.13 used QS alexandrite

laser with the mean session number of 7, and most patients

showed post-laser PIH. In our own experience using QSR laser

for ADM without any pretreatments, PIH was almost always

observed 2-4 weeks after the first laser treatment.

The typical color of ADM is grayish-brown2-4. It is more

brownish than typical nevus of Ota (blue-black, or slate-gray).

The reasons for the difference in color seem to be the existence

of epidermal hyperpigmentation and the location of dermal

melanocytes. In ADM, dermal melanocytes locates more superficial

(the upper dermis2) when compared to nevus of Ota (throughout

the entire dermis22). Although few reports have mentioned

about the epidermal hyperpigmentation of ADM in the past,

we confirmed epidermal hyperpigmentation in all specimens

examined in this study (Fig. 5). We consider that the existence

of epidermal (basal) melanosis is the reason for the difference

in response to laser treatment and incidence rate of PIH

between ADM and nevus of Ota. In addition, all biopsy specimens

showed disappearance of rete ridges, whereas surrounding

intact skin had normal-like rete ridges in some cases. This

finding may clinically mean suppression of epidermal turnover

and discharge of epidermal melanin, and may be related to

the epidermal hyperpigmentation seen in ADM, whereas the

reason for epidermal hyperpigmentation in ADM is unknown

and epidermal melanocytes in ADM are presumably abnormal

like melasma.

In this study, we confirmed histologically that accumulated

melanin granules around the basal layer were cleared up after

treatment with tretinoin and hydroquinone, but the melanin

deposits (dermal melanocytes) in the dermis appeared not

to change in ADM (Fig. 6). Taken together with our previous

studies18,23-25, this finding supports our previous hypothesis

for mechanism of this topical bleaching therapy; Tretinoin

acts as a discharger of epidermal melanin by accelerating

epidermal turnover and promoting keratinocytes proliferation,

while hydroquinone suppresses new melanin production by epidermal

melanocytes.

It is considered that the present combination therapy with

QSR laser and the aggressive bleaching treatment has the

following advantages: 1) High efficiency of the QSR laser

treatment in improving dermal pigmentation; After the pretreatment

removing epidermal pigmentation (basal melanosis), the laser

radiation can be expected to more efficiently get to the

dermis because the laser energy is thought not to be much

absorbed by epidermal melanins 2) Decreasing the rate of

PIH; We assume that, if there is a significant amount of

epidermal pigmentation, considerable inflammation would be

induced in the entire epidermis, resulting in occurrence

of PIH usually 2-4 weeks after laser irradiation. In this

sense, therefore, the pretreatment to discharge epidermal

melanins seems to be quite important. Indeed, with the bleaching

pretreatment, the frequency of PIH after initial laser treatment

was as low as 10.6 %. It was significantly lower than other

studies. In addition, PIH was not clearly detected after

the second or third laser treatment.

Nevus of Ota, which can usually be well treated by several

sessions of QSR laser, have predominantly dermal pigmentation.

This is because, unlike ADM, it does not have significant

epidermal pigmentation, which induces PIH after laser treatments

and makes it more difficult to treat consistently. Therefore,

we prefer the topical bleaching therapy with tretinoin and

hydroquinone for epidermal pigmentation, and QS lasers for

dermal pigmentation, with the exceptions of hyperkeratotic

lesions with such as solar lentigines on extremities and

trunks that we treat with QSR laser. It may be desirable

to perform laser treatments after pretreatment of epidermal

pigmentation for lesions with both epidermal and dermal pigmentation,

such as ADM and hyperpigmentation after atopic dermatitis.

The topical bleaching therapy can treat almost any kinds

of epidermal hyperpigmentation without hyperkeratosis including

PIH and melasma, which can not be treated with lasers.

For treatment of PIH after laser treatments, topical tretinoin

and hydroquinone appeared to be best as we and others13 did,

though the bleaching protocols are not the same. Otherwise,

we can wait for spontaneous clearance of PIH, but the clearance

is not guaranteed and intervals between laser sessions become

much longer such as 3-6 months12. PIH is one of the easiest

pigmented lesions to treat with the topical bleaching treatment17,

and, in this study, a mild treatment with tretinoin for only

2 weeks was usually sufficient, while hydroquinone was used

continually for over 1 month. Even if the pretreatment is

performed, intervals between laser treatments can be shortened

up to 6-8 weeks, therefore leading to shortening the total

treatment period compared with methods waiting for voluntary

disappearance of PIH.

Figures

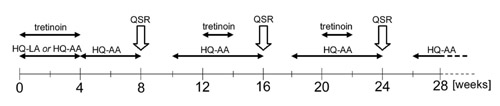

Fig. 1. A representative time

course of the combined treatment. Tretinoin is

used for 4 weeks in the initial bleaching pretreatment,

and for 2 weeks in the following pretreatments.

QSR laser treatment is performed 3 times, and

the total treatment period is 30 weeks.

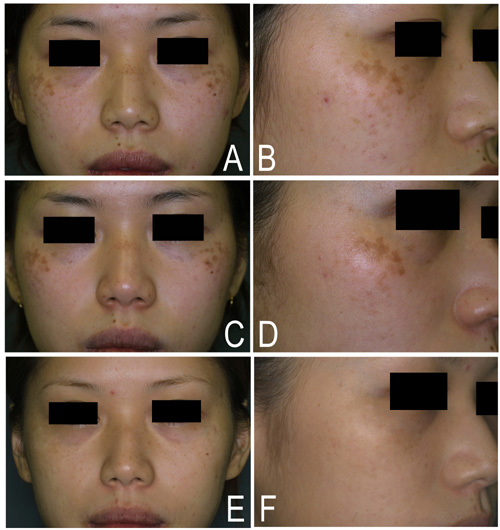

Fig. 2. Case1. A, B) Baseline

photos of a 24-year-old woman with ADM. C, D)

Just after the bleaching treatment with tretinoin

and hydroquinone. The color change of the macules

was moderate, but the histological change was

apparent as shown in Fig. 6. E, F) Six months

after the 3rd QSR laser treatment. Note the complete

clearance of pigmentation.

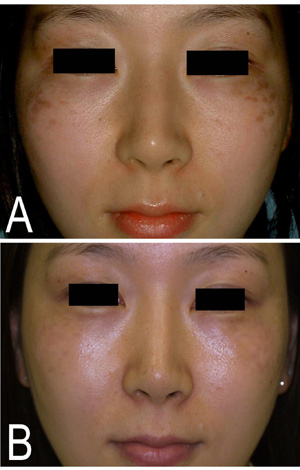

Fig. 3. Case2. A) A baseline view

of a 29-year-old woman with ADM. B) Ten months

after the 3rd QSR laser treatment. The clinical

result was evaluated as "excellent".

Fig. 4. Case3. A) A baseline view

of a 46-year-old woman with ADM. B) Three months

after the 3rd QSR laser treatment. The result

of the clearance was evaluated as "good".

Fig. 5. Histology of ADM before

treatments. Both sections demonstrated epidermal

hyperpigmentation around the basal layer, melanocytosis

in the upper dermis, disappearance of rete ridges,

and slight thinning of the epidermis. (Masson-Fontana

staining; 100X)

Fig. 6. Histology of ADM in case

1. (A) at baseline, and (B) just after the topical

bleaching pretreatment. A) At baseline, the section

demonstrated epidermal hyperpigmentation as well

as the scattered dermal melanocytes featuring

a highly pigmented, elongated dendritic appearance.

B) Just after the topical bleaching pretreatment,

epidermal pigmentation was significantly improved,

while the dermal menlanocytosis appeared not

to change at all. (Masson-Fontana staining; 200X)

References

1. Ota M, Tanino H. Naevus fuscocaeruleus

ophthalmo-maxillaris and melanosis bulbi. Tokyo

Iji Shinshi 1939;63:1243-5.

2. Hori Y, Kawashima M, Oohara K, Kukita A. Acquired, bilateral

nevus of Ota-like macules. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:961-4.

3. Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P. Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment

for acquired bilateral nevus of ota-like maculae: a long-term

follow-up. Lasers Surg Med 2000;26:376-9.

4. Polnikorn N, Tanrattanakorn S, Goldberg DJ. Treatment

of Hori's nevus with the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol

Surg 2000;26:477-80.

5. Lam AY, Wong DS, Lam LK, et al. A retrospective study

on the efficacy and complications of Q-switched alexandrite

laser in the treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like

macules. Dermatol Surg 2001;27:937-41.

6. Kuroki T, Noda H, Ichinose M, et al. Review of patients

with aquired bilateral nevus Ota-like macules. Journal of

Japan Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 1999;21:29-37.

7. Goldberg DJ, Nychay SG. Q-switched ruby laser treatment

of nevus of Ota. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1992;18:817-21.

8. Geronemus RG. Q-switched ruby laser therapy of nevus of

Ota. Arch Dermatol 1992;128:1618-22.

9. Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with

the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1745-50.

10. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of nevus of Ota by

the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg 1995;21:592-6.

11. Chan HH, Alam M, Kono T, Dover JS. Clinical application

of lasers in Asians. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:556-63.

12. Hidano A. Acquired, bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules.

J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;12:368-9.

13. Sun CC, Lu YC, Lee EF, Nakagawa H. Naevus fusco-caeruleus

zygomaticus. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:545-53.

14. Mizoguchi M, Murakami F, Ito M, et al. Clinical, pathological,

and etiologic aspects of acquired dermal melanocytosis. Pigment

Cell Res 1997;10:176-83.

15. Lee GY, Kim HJ, Whang KK. The effect of combination treatment

of the recalcitrant pigmentary disorders with pigmented laser

and chemical peeling. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:1120-3.

16. Yoshimura K, Harii K, Aoyama T, et al. A new bleaching

protocol for hyperpigmented skin lesions with a high concentration

of all-trans retinoic acid aqueous gel. Aesthetic Plast Surg

1999;23:285-91.

17. Yoshimura K, Harii K, Aoyama T, Iga T. Experience with

a strong bleaching treatment for skin hyperpigmentation in

Orientals. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:1097-108.

18. Yoshimura K, Momosawa A, Watanabe A, et al. Cosmetic

color improvement of the nipple-areola complex by optimal

use of tretinoin and hydroquinone. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:1153-8.

19. Hori Y, Takayama O. Circumscribed dermal melanoses. Classification

and histologic features. Dermatol Clin 1988;6:315-26.

20. Kunachak S, Kunachakr S, Sirikulchayanonta V, Leelaudomniti

P. Dermabrasion is an effective treatment for acquired bilateral

nevus of Ota-like macules. Dermatol Surg 1996;22:559-62.

21. Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P, Sirikulchayanonta V. Q-Switched

ruby laser therapy of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like

macules. Dermatol Surg 1999;25:938-41.

22. Hirayama T, Suzuki T. A new classification of Ota's nevus

based on histopathological features. Dermatologica 1991;183:169-72.

23. Yoshimura K, Tsukamoto K, Okazaki M, et al. Effects of

all-trans retinoic acid on melanogenesis in pigmented skin

equivalents and monolayer culture of melanocytes. J Dermatol

Sci 2001;27suppl1:68-75.

24. Yoshimura K, Uchida G, Okazaki M, et al. Differential

expression of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF)

mRNA in normal human keratinocytes induced by a variety of

natural and synthetic retinoids. Exp Dermatol, in press.

25. Yoshimura K, Momosawa A, Aiba E, et al. Clinical trial

of bleaching treatment with 10 % all-trans retinol gel. Dermatol

Surg, in press.

|