Abstract

Background: A prominent mandibular angle is a relatively

common aesthetic problem among Orientals, and reduction

angle-splitting ostectomy is now becoming a very popular

procedure in Asian countries. Although this operation

is usually performed on young patients, the same aesthetic

demands are also seen in the elderly.

Methods: In this report, we describe our experience

of angle-splitting ostectomy on five patients over 50

years old. The operation procedure was the same as performed

in young patients, and clinical results were assessed

with photos and 3D-CTs.

Results: The aesthetic results of the facial contours

were satisfactory, but patients usually showed postoperative

redundancy of the skin especially along the jaw line

because of the loss of bony protrusion laterally. Therefore,

3 of the 5 cases underwent subsequent SMAS cheek lift.

The inferior alveolar nerve was damaged in one case

partly due to an atrophied mandibular bone with loss

of molars and premolars, so more care should be taken

in elder patients.

Conclusions: Angle-splitting ostectomy can be safely

and effectively performed on the elderly when the surgeons

are aware of the risks and indications specific for

the elderly patients, and a multidisciplinary support

system is available.

Introduction

A prominent mandibular angle is a relatively common

aesthetic problem among Orientals, and reduction angle-splitting

ostectomy is now becoming a very popular procedure in

Asian countries1-3. As reported previously, most of

patients who undergo reduction mandibuloplasty are young,

and elderly patients are very rare.

It is of note that aesthetic problems related to a prominent

mandibular angle are twofold in the elderly. One is

the same as in younger patients: broadness of the lower

face with an angular contour gives a strong impression,

undesirable in most Asian females. This type of aesthetic

demand is seen in elderly as well as younger patients.

Another point is more specific to the elderly: rhytidectomy

in the elderly is generally less effective in Asian

patients with a prominent mandibular angle than in Caucasians.

Prominence of the mandible disturbs the smooth excursion

of lifting skin in the dissected cheek, and this problem

is frequently and specifically encountered in Asian

women4. In these contexts, reduction ostectomy of the

mandibular angle for the elderly is well justified,

although most previous publications mentioned only younger

cases.

In the past two years, we performed angle-splitting

ostectomy on five elderly Japanese patients over fifty

years old. Three of them had rhytidectomy afterwards

and one of the others is planning to. Some special considerations

should be required for managing these cases, and if

they are kept in mind, we believe that this operation

can be safely and effectively performed in elderly patients.

We herein describe our experiences in detail, and discuss

some features of this operation specific for the elderly

cases.

Materials and Methods

Patients

In the past two years, we performed angle-splitting

ostectomy on five Japanese patients over fifty years

old (Table 1). All of the patients had this operation

for a purely aesthetic purpose, and none had specific

craniofacial anomalies. Three of them had operation

of rhytidectomy several months later. None had simultaneous

ostectomy and rhitidectomy. We found no particular

risks for general anesthesia in these patients in

preoperative examinations, and all cases underwent

surgery under general anesthesia. We routinely suggested

patients to give 400 ml of their own blood at the

time of preoperative examinations for auto-transfusion,

and four of five patients did so.

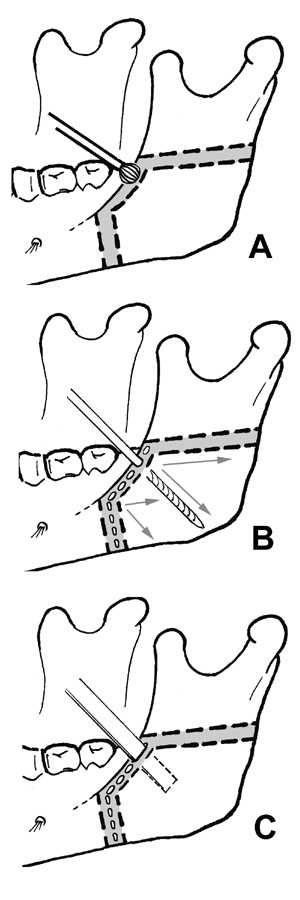

Operative Procedures

The operations were performed mostly according to

previous publications by Deguchi et al.2 and Han and

Kim3, with slight modifications. In brief, the oral

mucosa was incised along the mandibular ramus, from

the point just beside the parotid papilla to the first

molar. The lateral surface of the mandibular angle

was exposed by subperiosteal dissection. The caudal

end of the masseter muscle was carefully released

from the mandible, but we did not cut or resect the

muscle berry. A deep groove was hollowed out on the

lateral cortex using a round burr, along the upper

and anterior boundary of the ostectomized area (Fig.

1A). Several perforations were made using a Lindemann

drill burr (Downs Surgical, Sheffield, UK) from this

groove toward the posterior and inferior margin of

the mandible, in parallel with and just under the

lateral cortex, to avoid any unexpected malfracture

(Fig. 1B). Then, the lateral cortex of the angular

bone was ostectomized with a bone chisel. If necessary,

the tip of the angle can be additionally excised with

an oscillating saw (Fig. 1C). The released end of

the masseter muscle was left detached. Finally, a

Penrose drain was inserted, the oral mucosa was closed

with absorbable 4-0 sutures, and a pressure mask was

applied and left overnight. The Penrose drains were

removed a few days later.

Results

The splitting-angle ostectomy was performed successfully

in all cases. Avarage operation time was 2 hours and

50 minutes. Average amount of hemorrhage was 500 ml,

and the four patients who gave their own blood preoperatively,

underwent auto-transfusion just before finishing surgery.

No patients required blood transfusions from other

persons. No malfractures of the mandible body, ramus

or condyle occurred. The right inferior alveolar nerve

was unexpectedly damaged during the splitting ostectomy

in one patient (Case 5). In this case, the ramus was

atrophic, possibly due to previous extraction of the

molars and premolars. The nerve was repaired with

8-0 nylon sutures and fibrin glue.

Postoperative recovery of general conditions was uneventful,

and no patients exhibited circulatory or respiratory

problems. No hematomas or no local infections were

observed. Transient unilateral sensory disturbance

of the skin in the mental nerve area was observed

in two cases (in addition to Case 5), and slight paralysis

of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve

was seen for a few days in one case. Aesthetic outcomes

were quite satisfactory in all cases. Skeletal contours

of the lower face were significantly changed. Effects

of the facelift were remarkable in the three patients

who underwent subsequent rhytidectomy.

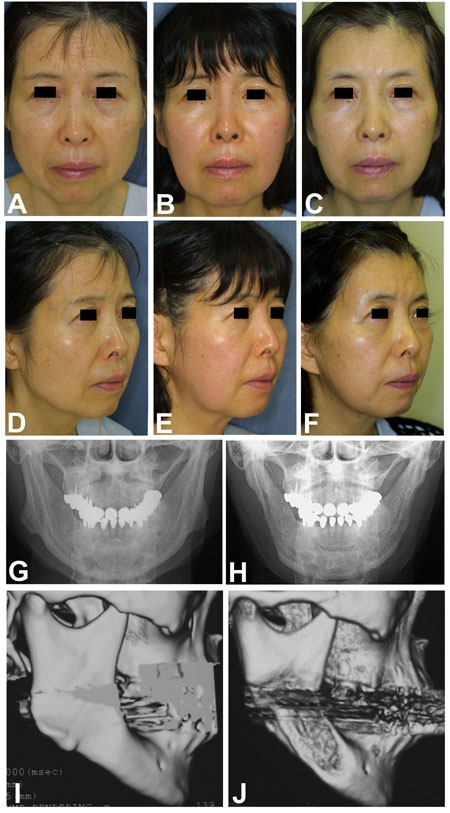

Case 1

A 55-year-old woman sought treatment for prominent

mandibular angle (Figs. 2A and 2D). She had a constant

complaint about the shape of her mandible from her

teenage. Also she wished to undergo a face-lift. She

had no special history of past illness. X-rays and

3D-CTs showed remarkable protrusion and lateral flaring

of the mandibular angle (Figs. 2G and 2I). The angle-splitting

ostectomy was performed under the general anesthesia,

and 5 x 2.5 cm fragments of the lateral cortex were

removed bilaterally. Postoperative X-rays and 3D-CTs

showed significant reduction of the lateral cortex

(Figs. 2H and 2J), and her facial contour was remarkably

changed two months after the ostectomy (Figs. 2B and

2E).

A rhytidectomy with radical SMAS lift was performed

three months after the ostectomy. The lifting was

very effective for reducing redundancy of the skin

in the mandibular area (Figs. 2C and 2F). No specific

problem was observed except slight and transient sensory

disturbance in her left lower lip. The patient was

very satisfied with the final result.

Case 2

A 65-year-old woman was referred to us for treatment

for her facial contour (Fig. 3A). She had been unhappy

with her angled face and low nose since childhood.

She had a history of asthma, but no attacks in the

last 10 years. A preoperative spirogram showed no

problems, and she underwent angle-splitting ostectomy

under general anesthesia. The angled contour was improved,

but the upper part of the angle was not completely

resected (Fig 3b). Seven months later, we performed

a correction of mandibular angle--through a facelift

incision with great care not to damage the submandibular

branch of the facial nerve-- together with an SMAS

facelift and insertion of silicone implants into her

nasal dorsum. The final result was very satisfactory

(Fig.3C).

Case 3

A 51-year-old housewife had a complaint about her

prominent zygoma and mandible (Figs. 4A and 4C). She

underwent a resection of the uterus myoma several

years ago, but had no other particular history. In

this case, the lateral flaring was not so remarkable,

but the whole mandibular angle was hypertrophic in

the preoperative 3D-CT (Fig. 4E). She underwent angle-splitting

ostectomy under general anesthesia. Postoperative

recovery was uneventful. A SMAS lift was performed

five months later, and the postoperative contour was

markedly improved (Figs. 4B, 4D and 4F).

Discussion

There have been a number of reports on surgical methods

for angular faces. This condition was historically

called "benign masseteric hypertrophy",

and resection of the masseter muscle as well as bone

was originally regarded as essential5,6. However,

angled appearance of the face in Orientals can be

primarily attributed to a lateral flaring of the bony

angle7. The masseter muscle, which always exhibits

tetanic contration, as do the calf muscles, can be

atrophied only by releasing the end of the muscle3,

and also by inducing temporal paralysis with Botulinus

toxin8. Therefore, the mandibular angle ostectomy

without muscle reduction can be a primary procedure

sufficient for this condition. Some authors reported

a simple full-thickness excision of the protruding

part of the bony angle1,7,9, which may often be accompanied

by an unnecessary change of SN/MP angle. Therefore,

a lateral cortical reduction by angle-splitting ostectomy

is now the first choice of operative options for the

majority of patients2,3.

In this paper, we described our experience of the

angle-spliting ostectomy in five aged Japanese women.

Most of the operative procedures are the same as in

younger patients, and the aesthetic results were quite

satisfactory. The final results were most dramatic

when the ostectomy was combined with subsequent rhytidectomy,

as seen in Cases 1, 2 and 3. It has been pointed out

that rhytidectomy in Asians requires special considerations,

because the facial skeletal contour in Orientals is

round and squared as Shirakabe et al. described in

the "baby model" paradigm4,10. Oriental

skin is thicker than that of Caucasians with abundant

extracellular matrices10, and this fact also contributes

to the difficulty of Asian rhytidectomy. In this sense,

after correcting angular skeletal contours with angle-splitting

ostectomy, facelift can be performed more easily in

Orientals with ideal clinical results. Baek et al.7

also reported a combination of angle ostectomy and

rhytidectomy in several patients, the two procedures

performed simultaneously in their cases. However,

we prefer two-stage operations with an interval of

several months for the following reasons. One reason

is to avoid lengthy operation time, considering that

Orientals need vigorous SMAS lift as noted above.

Delicate adjustment of the bony angle shape can be

achieved in the second operation through a facelift

incision as seen in Case 2--another advantage of our

two-stage strategy. We consider the most important

reason to be that sufficient lifting is likely impossible

in the one stage operation due to intraoperative swelling

caused by the ostectomy.

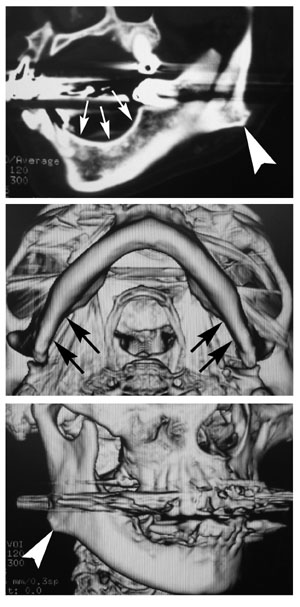

Several problems should be borne in mind when the

angle-splitting ostectomy is performed on the elderly.

Most important is atrophy of the mandible, as seen

in Case 5. In this case, the inferior alveolar nerve

was damaged during the splitting ostectomy partly

due to the thinness of the bony angle. As stated by

Moss and Salentijn11 in their "functional matrix"

concept, craniofacial bone remodeling is mainly controlled

by external mechanical stresses. The edentulous mandible

in the elderly often exhibits remarkable atrophy mainly

in the alveolus by the loss of stress through the

teeth12. In Case 5, the bilateral molars and premolars

were missing and the 3D-CT revealed atrophy and thinness

around the mandibular angle (Figs. 5A and 5B). However,

we can also detect in this CT a remarkable lateral

flaring of the angle, which causes a prominent mandibular

angle (Figs. 5B and 5C). The mechanisms by which the

functional matrix works are completely different between

the alveolus and the lateral flaring of the angle,

because the bone deposition in the lateral cortex

of the mandibular angle is considered to be affected

by the tention of the masseter muscle13. This is the

reason why a prominent mandibular angle can be observed

even in the edentulous atrophic mandible. We can treat

such cases with reduction mandibuloplasty, but special

care should be taken not to damage the inferior alveolar

nerve and to avoid malfractures. It is reported that

the mandibular canal remains intact around the angle

even in the completely edentulous mandible12, and

this fact supports our opinion that angle-splitting

can be safely performed if the surgeons are well acquainted

with the specific features of mandibular atrophy in

elderly patients. Preoperative 3D-CTs may be quite

informative for this purpose.

Other risks of the angle-splitting ostectomy include

hemorrhage from branches of the facial artery. We

encountered a relatively large amount of hemorrhage

in three patients. This risk can be minimized by preparation

of the auto-blood transfusion. Collaboration with

anesthesiologists is also essential for avoiding general

risks potentially serious in the elderly, and with

their help we did not experience any circulatory or

respiratory troubles pre- or post-operatively.

In conclusion, we believe the angle-splitting ostectomy

for the prominent mandibular angles can be safely

and effectively performed on elderly patients, if

the surgeon is well acquainted with the specific features

in elderly cases, and a multi-disciplinary support

system is available.

Legends

Fig.1 Illustrations of the operative procedures. (A)

A deep groove is made along the shaded area (upper

and anterior boundary of the ostectomy), using a round

burr. (B) Several perforations are made using a Lindemann

drill burr from this groove in various directions

(arrows). (C) The lateral cortex of the angular bone

is ostectomized with a bone chisel. The tip of the

angle is additionally excised with an oscillating

saw, if necessary.

Fig.2 Case 1. A 55-year-old woman. (A, D) Preoperative

appearance. (B, E) Two months after the ostectomy.

(C, F) Two months after the SMAS lift. (G) Preoperative

frontal cephalogram shows remarkable lateral flaring

of the mandibular angle. (H) Post-ostectomy cepharogram.

(I) Preoperative 3D-CT. (J) Post-ostectomy 3D-CT reveals

a successful reduction of the angle.

Fig.3

Case 2. A 65-year-old woman. (A) Preoperative appearance.

(B) Appearance after the angle-splitting ostectomy.

Some protrusion is left in the angle. (C) Final appearance,

1 year after the ostectomy and five months after the

SMAS lift. The angle shape was adjusted through the

facelift incision. She also underwent augmentation

of the nose at the secondary operation. Fig.3

Case 2. A 65-year-old woman. (A) Preoperative appearance.

(B) Appearance after the angle-splitting ostectomy.

Some protrusion is left in the angle. (C) Final appearance,

1 year after the ostectomy and five months after the

SMAS lift. The angle shape was adjusted through the

facelift incision. She also underwent augmentation

of the nose at the secondary operation.

Fig.4 Case 3. A 51-year-old woman.

(A,C) Preoeprative appearance. (B, D) Postoperative

appearance, 8 months after the ostectomy and three

months after the SMAS lift. (E) Preoperative 3D-CT

reveals remarkably hypertrophic angle of the mandible.

(F) Postoperative 3D-CT shows that the ostectomy was

effective.

Fig.5

Preoperative CT of the edentulous mandible of Case

5, a 69-year-old woman. (A) CT of the oblique plane

of the left mandibular angle. Note the lateral flaring

of the angle (arrowhead) even though the mandibular

body shows remarkable atrophy (arrows) due to the

extraction of the molars and premolars. (B) A caudal

view of the mandible by 3D-CT shows atrophy around

the angle (arrows). (C) A lateral view of the mandibular

angle by 3D-CT. The lateral flaring is obviously noted

(arrowhead). Fig.5

Preoperative CT of the edentulous mandible of Case

5, a 69-year-old woman. (A) CT of the oblique plane

of the left mandibular angle. Note the lateral flaring

of the angle (arrowhead) even though the mandibular

body shows remarkable atrophy (arrows) due to the

extraction of the molars and premolars. (B) A caudal

view of the mandible by 3D-CT shows atrophy around

the angle (arrows). (C) A lateral view of the mandibular

angle by 3D-CT. The lateral flaring is obviously noted

(arrowhead).

Table 1. Patient Profiles

Case

number age sex operation time bleeding (ml) auto-blood

transfusion intraoperative

nerve injury subsequent

face lift follow

-up

1 55 F 2h25m 400 + - + 1y11m

2 65 F 1h55m 100 - - + 1y2m

3 51 F 2h15m 560 + - + 8m

4 61 F 3h00m 670 + - - 6m

5 69 F 4h20m 770 + + - 3m

References

1. Baek, S. M., Kim, S. S., and Bindiger,

A. The prominent mandibular angle: preoperative management,

operative technique, and results in 42 patients. Plast

Reconstr Surg 83: 272, 1989.

2. Deguchi, M., Iio, Y., Kobayashi, K., and Shirakabe,

T. Angle-splitting ostectomy for reducing the width

of the lower face. Plast Reconstr Surg 99: 1831, 1997.

3. Han, K., and Kim, J. Reduction mandibuloplasty:

ostectomy of the lateral cortex around the mandibular

angle. J Craniofac Surg 12: 314, 2001.

4. Shirakabe, Y. The Oriental aging face: an evaluation

of a decade of experience with the triangular SMAS

flap technique in facelifting. Aesthetic Plast Surg

12: 25, 1988.

5. Adams, W. Bilateral hypertrophy of the masseter

muscle: An operation for correction (case report).

Br J Plast Surg 2: 78, 1949.

6. Ousterhout, D. K. (1991). "Mandibular width

reduction including the surgical treatment of benign

masseteric hypertrophy." Aesthetic contouring

of the craniofacial skeleton, D. K. Ousterhout, ed.,

Little, Brown, Boston, 451.

7. Baek, S. M., Baek, R. M., and Shin, M. S. Refinement

in aesthetic contouring of the prominent mandibular

angle. Aesthetic Plast Surg 18: 283, 1994.

8. Lindern , J.J., Niederhagen, B., Appel, T., Berge,

S., Reich, R.H. Type A botulinum toxin for the treatment

of hypertrophy of the masseter and temporal muscles:

an alternative treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 107:327,

2001.

9. Yang, D. B., and Park, C. G. Mandibular contouring

surgery for purely aesthetic reasons. Aesthetic Plast

Surg 15: 53, 1991.

10. Shirakabe, Y., Suzuki, Y., and Lam, S. M. A new

paradigm for the aging Asian face. Aesthetic Plast

Surg2003.

11. Moss, M. L., and Salentijn, L. The primary role

of functional matrices in facial growth. Am J Orthod

55: 566, 1969.

12. Polland, K. E., Munro, S., Reford, G., et al.

The mandibular canal of the edentulous jaw. Clin Anat

14: 445, 2001.

13. Cutting, C. B., McCarthy, J., G., and Knoze, D.

M. (1990). "Repair and Grafting of Bone."

Plastic Surgery Vol.1, J. G. McCarthy, ed., W.B.Saunders

Company, Philadelphia, 583.

|