| INTRODUCTION

The use of biodegradable dermal fillers has become

increasingly popular for facial rejuvenation, partly

replacing the conventional surgical procedures with

which long and painful recovery time is unavoidable.1,2

Although numerous kinds of materials have been used

as biodegradable dermal fillers in the last decade2-4,

hyaluronic acid and collagen appear to be the materials

of choice with convincing evidence of their safety

and efficacy2,4-9.

Most common adverse effects of injection of hyaluronic

acid and collagen previously known are bruising and

erythema5,8,10-13. These symptoms almost always resolve

within a week, with no residual complications. The

most serious side effect in the acute phase is localized

tissue necrosis, which is induced by mechanical interruption

of local vascularity and has been reported to occur

very rarely (9 in 10,000 cases who underwent collagen

implantation11). On the other hand, allergic changes,

abscess formation, and granulomatous changes are known

as adverse effects in the chronic phase11,13-15, though

they are less frequent.

Among the adverse effects of dermal fillers, the most

serious one always leading to resultant scar formation

is tissue necrosis. More than half of the reported

cases involved the glabellar region, while only 4%

of them involved the nose11. Only one case of arterial

embolization following the injection of dermal fillers

has been reported16. In this case, the patient underwent

hyaluronic acid injection (RestylaneR) and suffered

transient skin ulceration on the glabella; the ulceration

cured within weeks leaving no cosmetic blemish. Here,

we report a case who received injections of two kinds

of fillers at one time, hyaluronic acid gel (RestylaneR,

Q-Med, Sweden) and human-tissue-derived reconstituted

collagen matrix (ShebaR, Hansbiomed, Korea), and suffered

arterial embolization and distant skin necrosis of

the nasal ala. This is the first detailed report of

nasal alar necrosis associated with arterial embolization

following injection of dermal fillers.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old Japanese woman, who had no previous

history of cosmetic surgery, underwent injection of

RestylaneR for shaping the nasal tip contour, and

of ShebaR for wrinkle correction of the upper white

lip and the nasolabial fold and augmentation of the

upper vermillion. Nothing was injected into the nasal

ala. Immediately after the injection the patient had

a striking pain on the left side of the face, and

a few hours later noticed reddish discoloration from

the left side of the nose and the upper lip to the

glabellar region. By the third day from the onset,

blisters appeared at the left nasal ala. When the

patient consulted our hospital on the sixth day, a

gangrenous skin necrosis measuring 1 cm by 1.5 cm

was present on the left nasal ala. (Fig. 1).

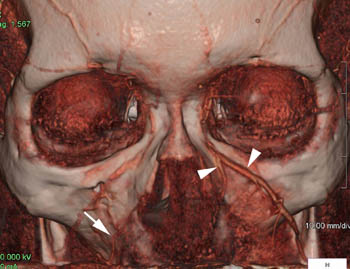

Three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography

(3D-CTA) was performed on the 9th day, which suggested

local occlusion of the left angular branch of the

facial artery (Fig. 2). Intravenous administration

of alprostadil (ProstandinR, 120 μg/day) was then

started and the surrounding erythema decreased with

time, but the necrosis extended to the surrounding

skin and subcutaneous tissue, which was surgically

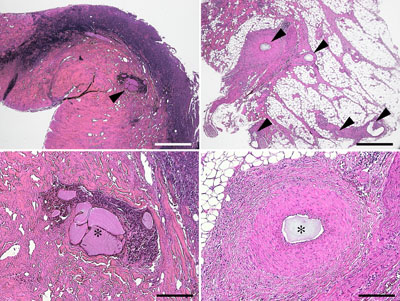

removed on the 12th day (Fig. 3). Histopathological

examination indicated intra-arterial and subdermal

deposition of foreign bodies as well as reactive changes

of the surrounding tissues (Fig. 4). The foreign bodies

were likely the injected dermal fillers, although

we could not identify whether it was Restylane or

Sheba. A full-thickness skin taken from the postauricular

area was grafted to the residual skin defect on the

43rd day, which was successfully accepted.

DISCUSSION

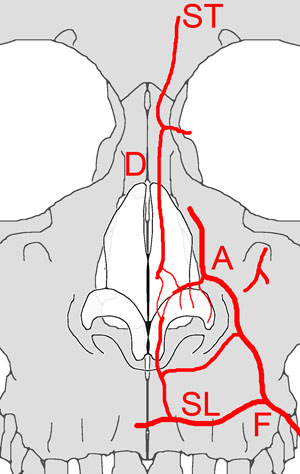

The blood supply of the nasal alar region depends

mainly on the facial artery, of which the running

course and branching are highly varied. Previous studies

demonstrated that the alar region is perfused by two

or three courses of blood supply17-22 (Fig. 5). The

most predominant course is the alar branch of the

facial artery, which branches directly from the angular

branch of the facial artery or from the superior labial

artery. The other courses are communicating arteries

coming through either the nasal dorsum or through

the columella. These arteries are anastomosed with

each other through the subdermal plexus17,18,21.

In the present case, the alar skin resulted in massive

necrosis, despite the absence of filler injection

into the ala. The histopathologic study of the biopsy

specimen of the ala revealed intradermal and intraarterial

foreign bodies (Fig. 4), which showed histopathologic

features comparable to hyaluronic acid or collagen

fillers as previously reported10,11,23,24. Arterial

embolization was suggested also by 3D-CTA that demonstrated

local occlusion of the angular branch of the facial

artery and compensatory dilation of collateral vessels

such as the infraorbital artery and its daughter branches

(Fig. 2). Sharp pain and the erythema observed on

the area nourished by the angular branch of the facial

artery in the early phase also suggested acute and

widespread embolization of the artery. Thus we diagnosed

the patient as suffering from arterial embolizations

of the angular branch and its daughter branches. Theoretically,

accidental injection of filler material into subcutaneous

small vessels caused arterial embolization, developing

into skin necrosis of particular regions.

The only reported case of arterial embolization induced

by hyaluronic acid injection involved the glabellar

region16. In addition, the glabella is the most common

region for local necrosis after bovine collagen injection11.

These cases, however, underwent dermal filler injection

at the same region as subsequent skin necrosis. In

the present case, massive skin necrosis occurred on

the nasal ala, although the patient had no injection

of dermal fillers in the area. Additionally, the patient

had no history of rhinoplasty that would likely affect

the condition of blood supply. Like the glabellar

region, the nasal ala may be a particular region in

which blood supply depends strongly on a single arterial

branch. Otherwise, collateral blood supply through

the nasal tip was blocked by the concurrent filler

injection to the nasal tip, which may be a critical

factor in this case. We could not distinguish whether

the foreign bodies found in the biopsy specimen were

RestylaneR or ShebaR. It also remains unknown whether

physical or biological characteristics of particular

products can influence the susceptibility toward vascular

embolization.

Although biodegradable dermal fillers have been proven

to be sufficiently safe, physicians should recognize

that they are still not devoid of serious side effects

as shown in this case. We think arterial embolization

is an adverse event not only of RestylaneR or ShebaR,

but also of any other dermal filler. The potential

risk of vascular embolization should be noted especially

when treating the nasal alar and perioral regions

as well as the glabellar region. Although accidental

intra-arterial injection of dermal fillers is apparently

rare, fillers should be injected into the dermis,

great care should be taken when injecting into the

subcutis to prevent intra-arterial injection, and

the anatomical feature of the facial artery and its

network should be correctly kept in mind.

REFERENCES

1. de Maio, M. The minimal approach: An innovation

in facial cosmetic procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg.

28: 295, 2004.

2. Narins, R. S., and Bowman, P. H. Injectable skin

fillers. Clin Plast Surg. 32: 151, 2005.

3. Sclafani, A. P., and Romo, T., 3rd. Injectable

fillers for facial soft tissue enhancement. Facial

Plast Surg. 16: 29, 2000.

4. Homicz, M. R., and Watson, D. Review of injectable

materials for soft tissue augmentation. Facial Plast

Surg. 20: 21, 2004.

5. Bauman, L. Cosmoderm/Cosmoplast (human bioengineered

collagen) for the aging face. Facial Plast Surg. 20:

125, 2004.

6. Narins, R. S., Brandt, F., Leyden, J. et al. A

randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of

the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus

Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol

Surg. 29: 588, 2003.

7. Douglas, R. S., Donsoff, I., Cook, T. et al. Collagen

fillers in facial aesthetic surgery. Facial Plast

Surg. 20: 117, 2004.

8. Friedman, P. M., Mafong, E. A., Kauvar, A. N. et

al. Safety data of injectable nonanimal stabilized

hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation.

Dermatol Surg. 28: 491, 2002.

9. Bowman, P. H., and Narins, R. S. Hylans and soft

tissue augmentation. In J. Carruther, A. Carruther,

Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology Series: Soft Tissue

Augmentation, 1st Ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Pp 33-54.

10. Duranti, F., Salti, G., Bovani, B. et al. Injectable

hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation.

A clinical and histological study. Dermatol Surg.

24: 1317, 1998.

11. Hanke, C. W., Higley, H. R., Jolivette, D. M.

et al. Abscess formation and local necrosis after

treatment with Zyderm or Zyplast collagen implant.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 25: 319, 1991.

12. Andre, P. Evaluation of the safety of a non-animal

stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA -- Q-medical, Sweden)

in european countries: A retrospective study from

1997 to 2001. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 18: 422,

2004.

13. Lowe, N. J., Maxwell, C. A., Lowe, P. et al. Hyaluronic

acid skin fillers: Adverse reactions and skin testing.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 45: 930, 2001.

14. Lupton, J. R., and Alster, T. S. Cutaneous hypersensitivity

reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid gel. Dermatol

Surg. 26: 135, 2000.

15. Shafir, R., Amir, A., and Gur, E. Long-term complications

of facial injections with Restylane (injectable hyaluronic

acid). Plast Reconstr Surg. 106: 1215, 2000.

16. Schanz, S., Schippert, W., Ulmer, A. et al. Arterial

embolization caused by injection of hyaluronic acid

(Restylane). Br J Dermatol. 146: 928, 2002.

17. Pinar, Y. A., Bilge, O., and Govsa, F. Anatomic

study of the blood supply of perioral region. Clin

Anat. 18: 330, 2005.

18. Jung, D. H., Kim, H. J., Koh, K. S. et al. Arterial

supply of the nasal tip in Asians. Laryngoscope. 110:

308, 2000.

19. Nakajima, H., Imanishi, N., and Aiso, S. Facial

artery in the upper lip and nose: Anatomy and a clinical

application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 109: 855, 2002.

20. Toriumi, D. M., Mueller, R. A., Grosch, T. et

al. Vascular anatomy of the nose and the external

rhinoplasty approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

122: 24, 1996.

21. Magden, O., Edizer, M., Atabey, A. et al. Cadaveric

study of the arterial anatomy of the upper lip. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 114: 355, 2004.

22. Rohrich, R. J., Muzaffar, A. R., and Gunter, J.

P. Nasal tip blood supply: Confirming the safety of

the transcolumellar incision in rhinoplasty. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 106: 1640, 2000.

FIGURE LEGENDS

Fig. 1. Views at the

first visit (6 days after injection). Gangrenous skin

necrosis was seen on the left nasal ala. Erythema

was seen on the whole area nourished by the angular

branch of the facial artery; the glabellar region,

the left side of the nose, and the left upper lip.

Fig. 2. Three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography

(3D-CTA) on the 9th day. 3D-CTA presented the local

occlusion of the left angular branch of the facial

artery. Compensatory dilation of collateral vessels

from the infraorbital artery was noted (arrowhead).

Contralateral angular branch of the facial artery

was patent and not dilated (arrow).

Fig. 3. Views before

(left), just after (center), and 4 weeks after (right)

debridement of the necrotic skin. Debridement was

performed on the 12th day and skin graft was performed

on 43rd day.

Fig. 4. Histology of debridement sample. Upper left:

low-power photomicrograph of the necrotic skin on

the nasolabial fold shows epidermal necrosis and intradermal

deposition of filler material (arrow). Lower left:

higher magnification of the upper left photograph

shows intradermal foreign bodies (?) accompanied by

infiltration of inflammatory cells. Upper right: low-power

photograph of subcutaneous tissue shows multiple intraarterial

embolizations (arrow). Lower right: higher magnification

ofupper right photograph shows intraarterial foreign

bodies (?) and thickening of the intima. Haematoxylin

and eosin stain. Bar = 800 μm for above and 200 μm

for below.

Fig. 5. Schematic view of the blood supply of the

nasal ala. The angular branch (A) of the facial artery

(F) runs along the nasolabial fold, branching off

the superior labial artery (SL). The alar branch is

a terminal branch of the angular branch, which is

the main feeding artery for the nasal ala. The superior

labial artery and the dorsal branch (D) of the superior

trochlear artery (ST) communicate with the alar branch

around the nasal tip.

|