|

Introduction

The treatment of acne in post-adolescent females often

fails1,2, although there are a number of treatments

with a relative high degree of effectiveness. Some

patients suffer from severe and repetitive acne, and

others have widespread occurrences of acne such as

on the chest and back. Inflammation, scars, and post-inflammatory

hyperpigmentation impair their appearance. The treatment

of acne is based on two separate concepts: 1) anti-symptomatic

treatments such as the use of chemical peeling, lasers,

and antibiotics3 and 2) inhibitory treatments such

as the use of oral retinoids and anti-androgen therapies

(retinoids also have symptomatic effects). Systemic

treatments are especially needed for treating cases

with severe, repetitive, or the widespread type of

acne throughout the body.

Hormonal anti-androgenic treatments could be most

effective for post-adolescent females to inhibit sebum

production and acne formation, though they can induce

side effects such as menstrual irregularity. Cyproterone

acetate, a synthetic progestin, is the first steroidal

anti-androgen agent widely used in the treatment of

advanced prostatic carcinoma and severe acne. However,

it was reported that long-term use of cyproterone

acetate can induce severe hepatocellular dysfunction

and potential carcinogenesis4,5, and the sale of the

agent was discontinued in Japan in1999. It is still

widely used in single-use form or in combination with

ethinyl estradiol, a contraceptive (e.g. Diane-35),

for severe acne in many western countries. Flutamide

is a non-steroidal anti-androgenic agent, recognized

as a competitive agonist of the androgen receptor

and a beneficial compound for the treatment of prostate

cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and hirsutism.

Despite its proven validity, hepatotoxicity due to

this agent has been reported and the use of this agent

is restricted6. In addition, flutamide inducing hepatotoxicity

is reported to be higher in Asians than in Caucasians7.

For this reason, in Japan, monthly blood tests for

checking liver function are required during the use

of flutamide. Spironolactone is well known as a diuretic

and has been used for over 20 years as a representative

antagonist of androgen in the treatment of acne and

hirsutism8,9. There have been several randomized studies

evaluating the efficacy of these agents in the treatment

of hirsutism10-13. Serious adverse drug-related experiences

and the discontinuation of therapy have been uncommon

in spironolactone therapy14, although gynecomastia15

and menstrual irregularities as side effects are frequently

seen accompanying high-dose use of spironolactone.

Other adverse side effects, such as lethargy, fatigue,

dizziness, or headache, were reported8,9,16,17.

As is well known, hormonal actions, serum hormone

levels, and side effects of hormonal agents frequently

differ among races or populations. As far as the Oriental

population is concerned, spironolactone appears to

be safest for treating acne among the three agents

discussed above with anti-androgenic action. The present

study was performed in order to assess the therapeutic

and side effects of oral spironolactone in Japanese

patients.

Patients and Methods

Spironolactone was administered orally to 139 Japanese

patients (ages 15 to 46 years, average 26.0 ± 6.8;

116 female and 23 male) suffering from acne at Ritz

Medical Clinic. Informed consent approved by IRB was

obtained from each patient or legal guardian. The

uses of other therapies for acne were not permitted

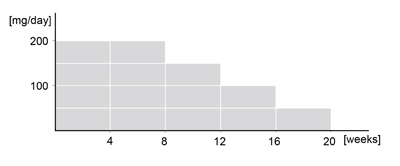

for the duration of the study. A 20-week course of

therapy was designed; the initial dose was 200 mg/day

for the first 8 weeks. After that, the doses were

progressively decreased by 50 mg every 4 weeks to

150 mg/day, 100 mg/day, and 50 mg/day (Fig.1).

The effectiveness of this treatment was evaluated

from the clinical results of 64 patients (all female)

who completed the 20-week treatment. A digital camera

was used to take clinical photographs before, during,

and after treatment. The therapeutic results were

graded according to the Consensus Conference on Acne

Classification18. Evaluations of improvement were

undertaken before and after treatment by two experienced

plastic surgeons who did not perform this treatment.

The investigators assessed each patient from his or

her photographs using a 3-point scale (2 = excellent

improvement, 1 = good improvement, and 0 = poor improvement).

In order to find related adverse events, we tested

the blood of the patients and collected before-and-after

data from 25 patients. Alanine transferase (ALT),

aspartate transferase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN),

creatinine (Cr), Na+, K+, Cl-, luteinizing hormone

(LH), dehydroepiandrostenedione sulfate (DHEAS), sex

hormone binding globulin (SHBG), total testosterone

(T), and free T in serum were measured, although not

all of the data were measured from all patients due

to the shortage of blood collected from some patients.

Statistical Analysis

Data were reported as mean ± standard error. The nonparametric

Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare clinical and

hormonal data from before and after treatment

Results

All 64 patients evaluated exhibited clinical improvement

(Table 1). Thirty-four patients (53.1%) showed fewer

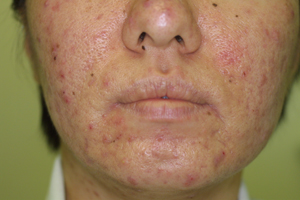

inflammatory spots (grade 2; Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Thirty

patients (46.9%) showed a decrease in new acne papules

(grade 1).

On the subject of side effects and complications,

about 80% of 116 female patients suffered from menstrual

irregularities. Five patients had no menstrual bleeding

during the first 3 months of treatment, and four had

severe menstrual irregularities. Both of these were

therefore given an intramuscular injection of estrogen

and progesterone to induce menstrual bleeding.

Among the 23 male patients, 3 (13%) showed gynecomastia

after 4 to 8 weeks of treatment (all 3 patients were

between 19 and 21 years old). Therefore, the administration

of spironolactone was discontinued to all male patients.

Other adverse side effects that had previously been

reported such as lethargy, fatigue, dizziness, or

headache were not observed in this trial. Changes

in urinary frequency were occasionally observed, however

these did not seem to reduce the patients’ quality

of life. Other side effects occurred in only a few

patients: drug eruptions were seen in three of 139

patients and edema in the lower extremities was also

seen in three.

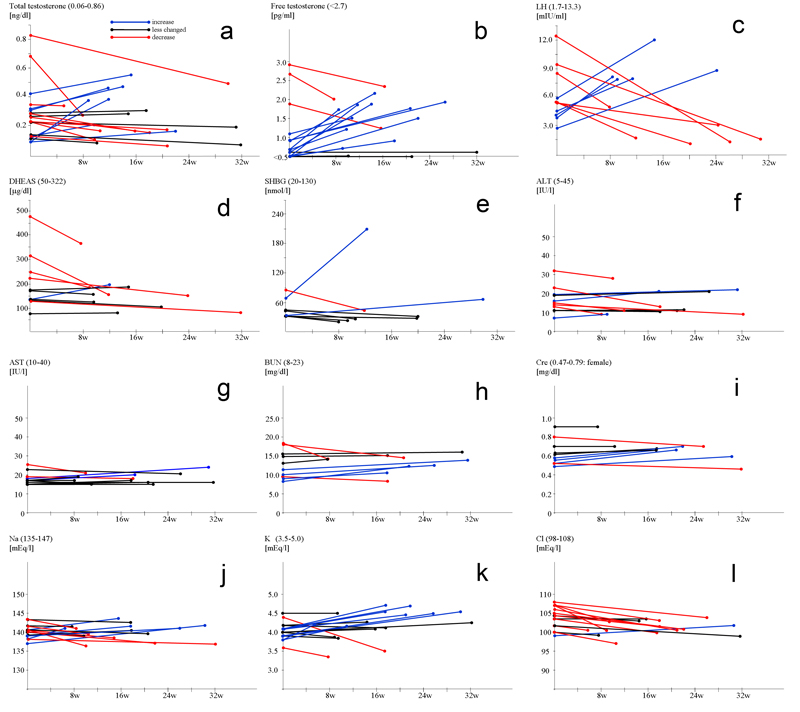

We analyzed the changes in serum hormones, laboratory

data, and blood levels of electrolytes resulting from

oral spironolactone treatment (Fig. 5). Regarding

testosterone (T) values, only a small number of patients

showed a high total T or free T level before treatment,

and a number of patients showed a low serum level

of total T or free T. There were no particular trends

in total T or free T before and after treatment, but

some patients with high total T or free T before treatment

tended to normalize their value after the treatment.

Similarly, patients with low total T or free T showed

a tendency to elevate their hormonal levels. The values

of LH, DHEAS, and SHBG of almost all patients were

within normal limits.

Indices of liver functions (ALT and AST) and those

of kidney functions (BUN and Cre) were not affected

by oral spironolactone. Unexpectedly, Na+ and K+ were

also not significantly affected by this urinary agent.

Only Cl- showed a significant decrease (p<0.05)

compared with the pretreatment value, however almost

all values were within normal limits.

Discussion

A key in treating acne, which almost always recurs,

is to perform both a preventive treatment as well

as a curative one. The results showed that oral spironolactone

is very effective for treating acne in Japanese females

without any serious side effects other than menstrual

irregularities.

There were no significant abnormalities in the pretreatment

data of serum TST and free TST in Japanese patients

suffering from severe acne. However, in this trial,

all female patients exhibited clinical improvement

in their acne after at least 4 months (usually 2 months

was sufficient) administration of oral spironolactone

without any other combined treatments. Thus, the results

strongly suggest that androgen signals affect acne

in almost all patients and factors other than serum

hormonal levels such as the expression level of androgen

receptors in the sebaceous glands have a critical

influence on sebum production and subsequent new acne

formation. The hypothesis may explain why some acne

patients do not respond to oral contraceptive treatments.

Oral contraceptives can reduce gonadotropins such

as LH and thereafter reduce T production and serum

level of T, but cannot block androgen signals at the

level of the androgen receptors. Thus, it is suggested

that oral spironolactone is advantageous for treating

acne compared with oral contraceptives. Gradually

decreasing spironolactone dosage can contribute to

preventing a recurrence of acne formation after the

treatment. Recurrences of acne occasionally occurred

several months after cessation of the administration

of oral spironolactone.

Some patients who also suffered from seborrheic dermatitis

on their faces showed improvement after the administration

of oral spironolactone. This probably results from

the inhibitory action of spironolactone for sebum

production by blocking androgen signals at the receptor

level. Indeed, almost all patients reported reduced

sebum discharge as soon as 2 weeks after starting

the oral spironolactone.

The mechanism of menstrual irregularities caused by

oral spironolactone is not clearly understood. After

the start of oral spironolactone administration, the

serum levels of T or dehydrotestosterone (DHT) could

be acutely elevated because androgen receptors are

competitively blocked by spironolactone. The excessive

T could then be transformed into estradiol, which

can induce endometrial hyperplasia and menstrual irregularities.

Gynecomastia can be induced in men for the same reason15.

As the 3 male patients with gynecomastia in this study

were between 19 and 22 years old, it is suggested

that this age range is most susceptible to suffer

from conversion from T to estradiol because of the

high serum level of T during this period. Oral treatment

with isotretinoin can be one important alternative

for male patients with severe acne19,20.

Most patients in our trial were satisfied with the

clinical results in spite of the menstrual irregularities

because they had been suffering from repetitive acne

for a long time and had lived a stressful life caused

by disfigurement. For 9 of 64 (14%) patients, a combined

injection of estrogen and progesterone was performed

for an effective induction of normal menstruation,

which was usually observed within 10 to 14 days after

the injection. Combined administration of contraceptives

can be useful for preventing possible pregnancy during

the treatment.

Other side effects such as itching and allergic eruptions

occurred in only a few patients. There were no abnormal

blood levels of electrolytes and laboratory data such

as ALT, AST, BUN, Cr, Na+, and K+ after administration

of the series of oral spironolactone. Only Cl- showed

a significant but minor decrease.

In summary, this study demonstrated that oral spironolactone

is quite effective for any type of acne in Asian females

and that this therapy is a good option, especially

for repetitive, severe, resistant, or widespread types

of acne in spite of its side effects such as menstrual

irregularities. Other additional therapies might be

helpful but not necessary for inhibiting new outbreaks

of acne. Male patients require an alternative treatment

such as oral isotretinoin. Oral spironolactone has

been used as a diuretic for a long time and its safety

has already been established for Asian people, although

two other hormonal agonists of acne therapy, cyproterone

acetate and flutamide, showed liver dysfunction in

Asians. Menstrual disturbance is common as an adverse

effect, but a compensatory hormonal injection is available

for inducing menstrual regularity.

References

1) Thiboutot D, Chen W. Update and future of hormonal

therapy in acne. Dermatology 2003;206,57-67.

2) Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post-adolescent

acne: a review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol

1997;136: 66-70.

3) Zouboulis CC, Martin JP. Update and future systemic

acne treatment. Dermatology 2003;206:37-53.

4) Parys BT, Hamid S, Thomson RG. Severe hepatocellular

dysfunction following cyproterone acetate therapy.

Br J Urol 1991;67:312-3.

5) Kasper P. Cyproterone acetate: a genotoxic carcinogen?

Pharmacol Toxicol 2001;88:223-31.

6) Wysowski DK, Freiman JP, Tourtelot JB, Horton ML

3rd. Fatal and nonfatal hepatotoxicity associated

with flutamide. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:860-4.

7) Takashima E, Iguchi K, Usui S, Yamamoto H, Hirano

K. Metabolite profiles of flutamide-induced hepatic

dysfunction. Biol Pharm Bull 2003;26:1455-60.

8) Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, Wise P. Oral

spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris

in women. Br J Dermatol 1986;115:227-32.

9) Messina M, Manieri C, Musso MC, Pastorino R. Oral

and topical spironolactone therapies in skin androgenization.

Panminerva Med 1990;32:49-55.

10) Lucky AW, Mcguire J, Rosenfield RL, Lucky PA,

Rich BH. Plasma androgens in women with acne vulgaris.

J Invest Dermatol 1983;81:70-4.

11) Vexiau P, Husson C, Chivot M, Brerault JL, Fiet

J, Julien R, et al. Androgen excess in women with

acne alone compared with women with acne and/or hirsutism.

J Invest Dermatol 1990;94:279-83.

12) Carmina E, Stanczyk FZ, Matteri RK, Lobo RA. Serum

androsterone conjugates differentiate between acne

and hirsutism in hyperandrogenic women. Fertil Steril

1991;55:872-6.

13) Slayden SM, Moran C, Sams WM Jr, Boots LR, Azziz

R. Hyperandrogenemia in patients presenting with acne.

Fertil Steril 2001;75:889-92.

14) Shaw JC, White LE. Long-term safety of spironolactone

in acne: results of an 8-year followup study. J Cutan

Med Surg 2002;6:541-5.

15) Satoh T, Itoh S, Seki T, Itoh S, Nomura N, Yoshizawa

I. On the inhibitory action of 29 drugs having side

effect gynecomastia on estrogen production. J Steroid

Biochem Mol Biol 2002;82:209-16.

16) Masahashi T, Wu MC, Ohsawa M, Asai M, Ichikawa

Y, Hanai K, et al. Spironolactone therapy for hyperandrogenic

anovulatory women--clinical and endocrinological study.

Nippon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi 1996;38:95-101.

17) Shaw JC. Low-dose adjunctive spironolactone in

the treatment of acne in women: a retrospective analysis

of 85 consecutively treated patients. J Am Acad Dermatol

2000;43:498-502.

18) Pochi PE, Shalita AR, Strauss JS, Webster SB,

Cunliffe WJ, Katz HI, et al. Report of the Consensus

Conference on Acne Classification. Washington, D.C.,

March 24 and 25, 1990.J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:495-500.

19) Ng PP, Goh CL. Treatment outcome of acne vulgaris

with oral isotretinoin in 89 patients. Int J Dermatol

1999;38:213-6.

20) Cooper AJ; Australian Roaccutane Advisory Board.

Treatment of acne with isotretinoin: recommendations

based on Australian experience. Australas J Dermatol

2003;44:97-105.

Legends

Figure 1. Protocol of oral spironolactone administration.

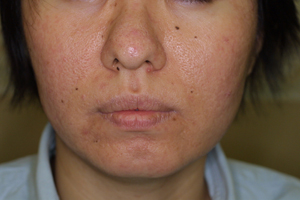

Figure 2. 27-year-old female with

acne vulgaris from the jawline to the neck who did

not improve by repeated AHA peeling and oral antibiotics.

(a) Before treatment. (b) After 20 weeks of oral spironolactone

(grade2, fewer inflammatory spots).

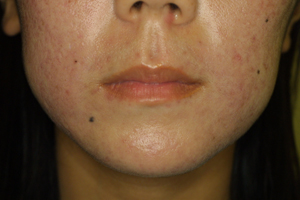

Figure 3. 31-year-old female with

acne vulgaris and seborrheic dermatitis on the whole

face. (a) Before treatment. (b) After 4 months of

oral spironolactone (grade 2). Sebum discharge was

markedly reduced and seborrheic dermatitis and acne

were both improved.

Figure 4. 28-year-old female with

acne vulgaris and severe sebum discharge. (a) Before

treatment. (b) After 4 months of oral spironolactone

(grade 2).

Figure 5. Data of blood tests before

and after administration of oral spironolactone: (a)

Total T, (b) Free T, (c) LH, (d) DHEAS, (e) SHBG,

(f) ALT, (g) AST, (h) BUN), (i) Cre, (j) Na+, (k)

K+, and (l) Cl-. Increased or decreased data by more

than 10 % of initial values were shown as blue or

red lines, respectively. Free testosterone showed

significant increases (p<0.05) and Cl- showed significant

decreases (p<0.05) compared with pretreatment values,

however almost all values were within normal limits.

LH, DHEAS, SHBG, ALT, AST, BUN, Cre, Na+, and K+ did

not show any significant differences.

Table 1. 3-point scale results. 2

= excellent improvement, 1 = good improvement, and

0 = poor improvement. The excellent feature showed

fewer inflammatory spots.

|