| INTRODUCTION

In Caucasians, the most common complaints about photoaged

skin are fine wrinkles and telangiectasia, but these

complaints are less common in populations with darker

skin, such as Asians. In Asians, hyperpigmentation

is the most common cosmetic complaint, but a standard

strategy for treating hyperpigmented skin lesions

has not been established. We have found that aggressive

use of topical tretinoin (0.1-0.4%) along with hydroquinone

(RA-HQ therapy) can successfully treat various skin

hyperpigmentation conditions in Asians.1-8 Although

the bleaching protocol we routinely use requires two

steps (a bleaching step and a healing step), and severe

but transient adverse skin reactions are possible,

this protocol is quite effective in removing epidermal

pigmentation. The rationale for this protocol is that

tretinoin reduces epidermal melanin by accelerating

epidermal turnover and promoting keratinocyte proliferation,

while hydroquinone acts as a suppresser of melanogenesis

by epidermal melanocytes.5,6,9 It is especially useful

for treating pigmented lesions that are not effectively

treated by lasers, such as melasma, postinflammatory

hyperpigmentation (PIH), and pigmented nipples/areolas.

Unfortunately, this bleaching protocol has no effect

on dermal pigmentation. In addition, hyperkeratotic

lesions are not a good indication for this protocol

because the thickened horny layer prevents penetration

and absorption of the agents. Therefore, in order

to treat every kind of hyperpigmented lesion, we have

to additionally use Q-switched lasers or CO2 lasers

to complement the bleaching protocol. Q-switched ruby

laser (QSR) use can be combined with topical treatment

for synergistically treating skin lesions when both

epidermal and dermal pigmentation are present, as

in acquired dermal melanocytosis (ADM),5,6,8 friction

melanosis, and pigmented cosmetic dermatitis. Depending

on their severity, hyperkeratotic lesions can be treated

primarily with QSR or CO2 laser irradiation.

In order to establish a therapeutic strategy that

addresses a wide range of hyperpigmented conditions,

we used topical bleaching treatment, QSR, CO2 lasers,

or combination treatment to treat patients in our

clinic, and analyzed 59 histological specimens from

49 patients. Clinical diagnosis identified 17 types

of lesions, which included conditions rarely described

as treatment targets. This analysis led us to propose

a new classification system for hyperpigmented conditions

based on histological features. Based on our clinical

experience treating hyperpigmented lesions and our

proposed classification system, we also present a

comprehensive therapeutic strategy for treating pigmented

skin conditions.

METHODS

Fifty-nine biopsies were taken from 49 Japanese female

patients (4 males and 45 females, age ranged from

16 to 60 (ave. = 36.16)) with hyperpigmented skin

lesions after informed consent using an IRB-approved

protocol. The lesions were clinically diagnosed as

follows: ADM (n =12); solar (senile) lentigines (n

= 8); lichen pilaris (n = 4); ripple/reticulate hyperpigmentation

in atopic dermatitis (RHAD) (n = 7); nevus spilus

(cafe au lait macules) (n = 4); pigmented contact

dermatitis (n = 4); pigmented nipple areolar complex

(PNAC) (n = 3); pigmentatio petaloides actinica (PPA)

(n = 4); ephelides (n = 2); friction melanosis (n

= 2); periorbital hyperpigmentation (n = 2); nevus

of Ota (n = 2); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

resulted from a single inflammatory event (PIH-S)

(n = 1); seborrheic keratosis (n = 1); melasma (ML)

(n = 1); pigmented external genitalia (n = 1); and

erythromelanosis follicularis faciei et colli (EFFC)

(n = 1). In addition, 10 samples were taken from 10

patients at baseline and during RA-HQ therapy; these

lesions included diagnoses of solar lentigines (n

= 1), lichen pilaris (n = 2), nevus spilus (n = 1),

pigmented contact dermatitis (n = 2), PNAC (n = 1),

RHAD (n = 1), ADM (n = 1), and PPA (n = 1).

Biopsied tissue was fixed in 4% buffered neutral formaldehyde

solution and embedded in paraffin for sectioning.

The sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and

Fontana-Masson stains. The pathological examination

focused on the existence of hyperkeratosis and the

location (layers) of melanin deposits or melanocytes,

since these two factors determined our therapeutic

strategy. Comparing samples obtained before and during

treatment, morphological alterations due to the RA-HQ

therapy were observed.

Details of the RA-HQ therapy protocol were described

previously.4-6 Briefly, the protocol consisted of

a bleaching phase and a healing phase. We originally

prepared 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4% tretinoin aqueous gels

and an ointment with 5% hydroquinone. For bleaching,

tretinoin was first applied only to the pigmented

area with a cotton tip applicator, and then hydroquinone

was applied to the larger area surrounding the lesion

(the whole face, for example). Initially, the application

was done twice a day, depending on skin reactions

such as erythema and scaling. When sufficient reduction

in pigmentation was obtained, the application of tretinoin

was discontinued. The duration of this phase was 2

to 6 weeks. For healing, hydroquinone alone was applied

twice a day until the erythema disappeared completely;

the duration of this phase was usually 4 weeks.

RESULTS

Biopsies of pigmented lesions

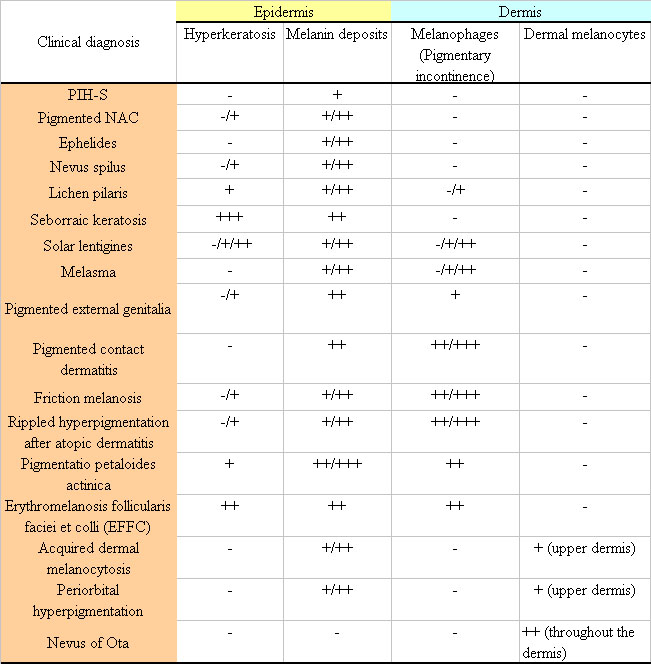

The histological characteristics and diagnoses of

the biopsied samples are summarized in Table 1. Clinical

appearance and histology of representative cases of

each morbidity are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Horny layers

In general, dermatoses located on the trunk and extremities

rather than on the face have a physiological tendency

toward hyperkeratosis. In agreement with this, in

pigmented lesions located on the body, i.e. on the

nipples/areola or on the external genitalia, the horny

layer was relatively thicker than for pigmented dermatoses

on the face. Solar lentigines and relatively flat

seborrheic keratoses resembled each other histologically.

Both were characterized by distinctive hyperkeratosis,

which was more obvious in lesions located on areas

other than the face. Note that in solar lentigines,

mild hyperkeratosis was observed even in lesions that

appeared flat. Lichen pilaris and EFFC also showed

mild hyperkeratosis, but the hyperkeratosis was more

distinctive in lichen pilaris. This difference in

the degree of hyperkeratosis was greater than expected.

In EFFC, the epidermis was acanthotic and hyperkeratotic

without parakeratosis, and follicular hyperplasia

with follicular plugging was also observed. No other

dermatoses investigated in this study showed hyperkeratosis.

Epidermal pigmentation

Epidermal pigmentation was enhanced in all the morbidities

in this study except for the nevus of Ota case. The

degree of epidermal melanin pigmentation varied among

the morbidities, and substantial differences were

found between cases.

Dermal pigmentation

Dermal melanosis (melanin incontinence) was observed

in some of the morbidities. Lesions resulting from

chronic or repeated inflammation, such as pigmented

contact dermatitis, friction melanosis, RHAD, and

PPA, showed breakdown of the dermo-epidermal junction

and severe dermal melanosis (deposits of melanophages)

in the upper dermis. Some melanophage deposits in

the upper dermis were also seen in cases of melasma

and solar lentigines, although degenerative changes

of the dermo-epidermal junction were not detected.

ADM and periorbital hyperpigmentation (a subtype of

ADM) had dermal melanocytes with a highly pigmented,

elongated dendritic appearance in the upper dermis,

while dermal melanocytes were scattered throughout

the dermis in nevus of Ota. In several morbidities

such as PIH-S, ephelides, and nevus spilus, dermal

pigmentation, either melanosis or melanocytosis, was

not detected irrespective of the degree of epidermal

pigmentation.

Samples taken during RA-HQ treatment

The histological and clinical manifestations of representative

cases of hyperpigmentation are shown in Figures 3

and 4. In sections obtained during RA-HQ therapy,

substantial epidermal hyperplasia, dramatic reduction

of melanin deposits around the basal layer, and temporal

enhancement of parakeratosis were consistently observed

(Figure 3B and D). These changes were most likely

a result of enhanced basal keratinocyte mitosis and

accelerated turnover of the epidermis. Epidermal pigmentation

was significantly reduced, while dermal melanophages

or melanocytes, if any, appeared unchanged (Figure

4B and D). The clinical observations agreed with the

histological findings. In lesions without dermal pigmentation

involvement, the pigmented color was clinically improved

(Figure 3E), while in lesions with dermal pigmentation,

the color change was usually moderate (Figure 4C)

until laser therapy was also used (Figure 4E).

DISCUSSION

Hyperpigmentation in the epidermis and dermis

Although the degree of pigmentation differed among

both morbidities and cases, the mechanisms underlying

melanin deposits in the epidermis can be understood

as follows. Epidermal melanin is continuously provided

to keratinocytes by melanocytes located in the basal

layer, transported to the stratum corneum by keratinocyte

turnover, and finally removed by stratum corneum sloughing.

In healthy skin, the total amount of epidermal melanin,

the main determinant of skin color, is the result

of the balance between production and discharge of

melanin. Production of epidermal melanin is regulated

by the genetic makeup and gene expression profile

of the melanocytes located in the basal layer, but

production can be enhanced by external factors such

as UV irradiation10 and inflammation. Skin phototype

is determined by the genetic makeup of melanocytes,

which is modified by genetic transformation of melanocytes

in morbidities such as solar lentigines11 and PPA.12

Melanin production can be suppressed by agents such

as hydroquinone that are toxic to melanocytes or that

inhibit melanocytes. On the other hand, the discharge

of epidermal melanin is determined mainly by epidermal

turnover, which can be increased by topical retinoids.

On the contrary, external factors such as topical

corticosteroids and aging can attenuate melanin discharge.

The regulatory mechanism of epidermal pigmentation

(skin color) is a key concept for establishing our

bleaching strategy to epidermal hyperpigmentation;

that is a combined use of tretinoin (a discharge enhancer)

and hydroquinone (a production suppressor).

In morbidities such as ephelides,11 nevus spilus,13

melasma,14,15 lichen pilaris, and EFFC,16,17 melanin

production is pathologically enhanced. In addition

to the underlying genetic factors, PNAC and external

genitalia are also influenced by hormones and topical

inflammation, such as that induced by the friction

caused by clothing.18 In solar lentigines and PPA,

UV irradiation induces genetic alterations in melanocytes,

though other internal and external factors can also

be pathogenetic.10,19 On the other hand, PIH-S is

the result of an external factor: in this condition,

melanogenesis is temporally enhanced due to an inflammatory

event. PIH-S usually involves only epidermal hyperpigmentation

without degenerative changes in the dermo-epidermal

junction, and tends to gradually disappear, but occasionally

it can persist for a long time.

Dermal pigmentation is influenced by another mechanism.

Although melanophages are occasionally present in

the normal dermis of Asians,20 they are mainly observed

in pigmented lesions with a grayish appearance known

as areas of “pigmentary incontinence.”21,22 Histologically,

pigmentary incontinence is caused by melanosome translocation

from the epidermis to the dermis, usually following

dermo-epidermal junction damage. Pigmented contact

dermatitis,23 friction melanosis,24 and RHAD25,26

are caused by repeated inflammatory events, which

induce repeated hypermelanogenesis and degeneration

of the dermo-epidermal junction, and result in scattered

melanophages located in the upper dermis. Our results

confirmed the histological features of these lesions,

and also revealed that some lesions classified as

solar lentigines and melasma also have melanophages

in the upper dermis without apparent dermo-epidermal

damage; the pigmentary incontinence of these lesions

may result from inflammatory events or excessive UV

irradiation encountered after the onset of the lesion.

In acquired dermal melanosis and periorbital hyperpigmentation,

there are ectopic and aberrant melanocytes in the

upper dermis (dermal melanocytosis); these conditions

can be distinguished from the pigmented lesions accompanying

dermal melanosis (pigmented incontinence) described

above.27 Nevus of Ota,28 nevus of Ito,29 and Mongolian

spots29 are known to have aberrant melanocytes throughout

the dermis.

Treatment-oriented histological classification

of hyperpigmented lesions

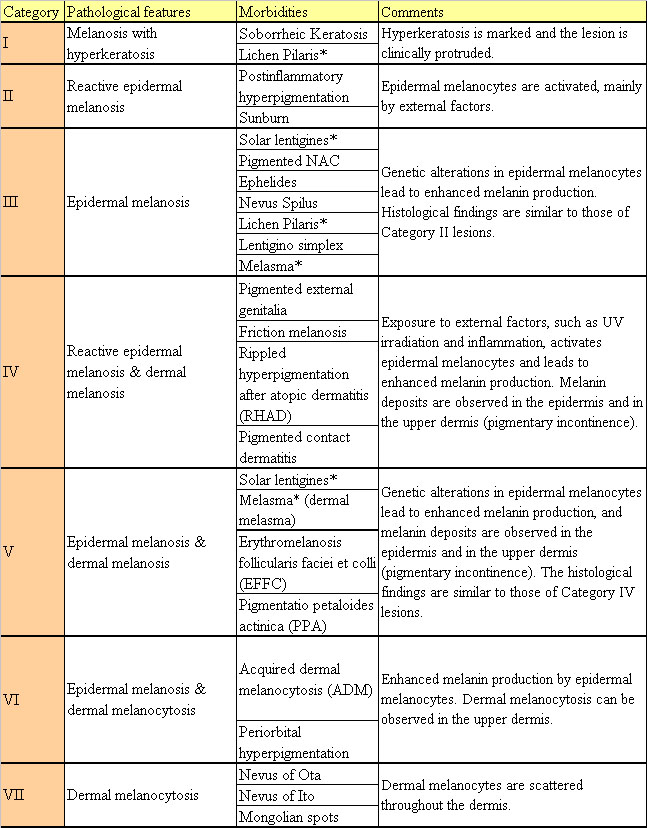

Based on the features of hyperkeratosis and epidermal

and dermal pigmentation discussed above, we propose

a new classification system for pigmented dermatoses;

diagnosis and histological features of each Category

are summarized in Table 2.

Morbidities with apparent hyperkeratosis are classified

in Category I; our strategy suggests that these lesions

should be treated with CO2 lasers. Based on the location

of the pigmentation, the character of the pigmentation

(melanosis or melanocytosis), and the melanocyte activity

(genetically upregulated or temporally upregulated),

lesions can be placed into Categories II to VII. Category

II and III include only epidermal hyperpigmentation

and Category VII includes only dermal hyperpigmentation,

while Categories IV to VI includes lesions with both

epidermal and dermal hyperpigmentation. Melanocytes

may be temporally upregulated by local inflammatory

events such as dermatitis, scratching, and UV irradiation

(Categories II and IV), while melanocytes have undergone

genetic changes leading to upregulation (Categories

III and V). The epidermal hypermelanosis observed

in lesions in Category VI may be due to stimulatory

effects of melanocytes localized in the upper dermis.4,6

Therapeutic strategy for pigmented lesions

based on their histological characteristics

Based on our classification system for pigmented skin

lesions, we have broadened the indications for our

therapeutic strategy. This therapeutic strategy involves

CO2 laser therapy, QSR laser irradiation, and topical

bleaching treatment (RA-HQ therapy), and is schematically

summarized in Figure 5. RA-HQ treatment accelerates

the removal of accumulated melanosomes in the epidermis

and replaces them with much less pigmented cells.

QSR laser irradiation not only reduces dermal melanosis

and melanocytosis, but also removes the pigmented

and hyperkeratotic epidermis associated with solar

lentigines. The former can also be accomplished using

a Q-switched Alexandrite laser, and the latter can

be accomplished with other lasers, such as the Q-switched

ND:Yag laser. A CO2 laser was used to treat lesions

with excessive hyperkeratosis (Category I lesions)

which could not be effectively treated with a QSR

laser. Hyperkeratotic lesions need to be treated with

lasers: because the thickened horny layer prevents

percutaneous absorption of topical ointment, RA-HQ

therapy does not work.

Lesions in Categories II and III are treated only

with topical RA-HQ therapy, except for solar lentigines

with hyperkeratosis. The treatment usually needs to

be performed repeatedly for melasma.4 PIH-S does not

recur after treatment, but ephelides, lentigo simplex,

and nevus spilus (cafe au lait macules) tend to reappear

within a few months unless topical hydroquinone is

used for post-treatment maintenance. Although the

RA-HQ therapy cannot treat dermal pigmentation and

hyperkeratotic lesions, it can be used as a pre-treatment

for QSR laser irradiation in treating Categories IV

to VI lesions. It can also be used after QSR laser

treatment, because it is quite effective for treating

the PIH frequently seen after QSR laser treatment

of darker-colored skin.

A critical difference between lesions in Category

IV to VI and those in Category VII is the extent of

epidermal pigmentation, which determines the beneficial

and adverse effects of QSR laser on dermal pigmentation.

If the lesion has only dermal melanocytosis (Category

VII), it can be effectively treated with repeated

sessions of QSR laser irradiation alone.30,31 However,

the sole use of Q-switched laser irradiation failed

in the treatment of morbidities with both epidermal

and dermal pigmentation (Categories IV to VI), ,resulting

in high frequency of PIH and/or depigmentation.32-34

We believe that, in these morbidities, epidermal melanin

deposits obstruct laser irradiations to dermal pigmentation

as competing chromophores; laser irradiation thus

induces considerable inflammation in the epidermis

and, consequently, severe PIH results especially in

patients with darker-colored skin.6 To overcome these

problems, we propose that topical bleaching be performed

prior to QSR laser therapy. The pretreatment can be

applied not only to ADM, but also to other skin conditions

with both epidermal and dermal pigmentation, such

as friction melanosis, pigmented contact (cosmetic)

dermatitis, and RHAD (lesions in Categories IV to

VI; Figure 4). For Category VI lesions (dermal melanocytosis),

the combination of RA-HQ treatment and QSR laser must

usually be performed 2 or 3 times, while only one

QSR session is usually needed for treating lesions

in Categories VI and V (dermal melanosis).

CONCLUSONS

We refined a strategy for treating hyperpigmentation

by studying lesion histology and by reviewing our

extensive clinical experience in treating Asian skin.

Here is our proposed standard strategy: first, treat

epidermal pigmentation with RA-HQ, unless the lesion

has hyperkeratosis; second, treat dermal pigmentation

without epidermal hypermelanosis with repeated QSR

laser irradiation; third, treat dermal pigmentation

with substantial epidermal pigmentation with a combined

RA?HQ treatment and QSR irradiation; fourth, repeat

each session as needed. We believe that the classification

system and the histology-based treatment principles

proposed in this study may be helpful for establishing

a standardized treatment algorithm for hyperpigmented

skin lesions, especially in Asians.

Table 1. A summary of the histological characteristics

of samples stained with Fontana-Masson stain.

Clinical diagnosis Epidermis Dermis

Hyperkeratosis Melanin deposits Melanophages (Pigmentary

incontinence) Dermal melanocytes

Table 2. Proposed 7-category classification system

for hyperpigmented lesions

* Morbidities classified into two Categories.

Figure legends

b.jpg)

Figure 1. Hyperpigmented lesions in Asians: clinical

manifestations.

(A) Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation resulting from

a single inflammatory event. (B) Pigmented nipple/areola.

(C) Ephelides. (D) Nevus spilus. (E) Lichen pilaris.

(F) Seborrheic keratoses. (G) Solar lentigines. H)

Melasma. (I) Pigmented external genitalia. (J) Pigmented

contact dermatitis. (K) Friction melanosis. (L) Ripple

hyperpigmentation in atopic dermatitis. (M) Pigmentatio

petaloides actinica. (N) Erythromelanosis follicularis

faciei. (O) Acquired dermal melanosis. (P) Periorbital

hyperpigmentation. (Q) Nevus of Ota.

b.jpg)

Figure 2. Hyperpigmented lesions in Asians: histological

findings.

Specimens were obtained from the lesions shown in

Figure 1. Photos A through Q: original magnification

×100. Photos O’, P’, and Q’: corresponding ×200 magnification

photos of specimens O, P, and Q.

b.jpg)

Figure 3. A 26-year-old-woman with pigmented nipple-areola

complex. (A) At baseline, the nipple-areola complex

showed dark brown hyperpigmentation. (B) Histological

examination revealed epidermal pigmentation. (C) Two

weeks after starting bleaching treatment with 0.2%

tretinoin and 5% hydroquinone, the hyperpigmentation

had improved. Some tretinoin-associated erythema was

observed. (D) Histological examination revealed hyperplasia

of the epidermis. Epidermal pigmentation was highly

reduced. (E) Eight weeks after starting treatment

(final result). For 4 weeks, 0.2% tretinoin was used

together with 5% hydroquinone, followed by treatment

with 5% hydroquinone alone for 4 weeks. Pigmentation

improved and no post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation

was observed.

b.jpg)

Figure 4. A 56-year-old woman with pigmented contact

(cosmetic) dermatitis. (A) At baseline, the patient

showed dark brown or dark grey macules distributed

symmetrically on a wide area of the face. (B) Histology

at baseline. The dermo-epidermal junction was severely

damaged and a number of melanosomes were found in

the upper dermis (pigmentary incontinence). (C) At

8 weeks, just after the topical bleaching treatment

with 0.1 and 0.4 % tretinoin and 5% hydroquinone,

the pigmentation was reduced with slight erythema,

but the macules still had a grayish color. (D) Histology

at 8 weeks. Epidermal pigmentation was significantly

improved, while the dermal melanocytosis appeared

not to change at all. (E) Clinical appearance at 20

weeks. QSR irradiation was performed to reduce dermal

melanosis at 8 weeks. Four weeks after the QSR irradiation,

RA-HQ therapy was performed again: 4 weeks of the

bleaching phase and 4 weeks of the healing phase.

b.jpg)

Figure 5. Schematic summary of our therapeutic strategy

for pigmented lesions.

A treatment protocol is suggested for lesions in each

Category (I to VII) except for Category II, which

was divided into three subclasses: solar lentigines,

melasma and others. Solar lentigines frequently have

a thicker horny layer, so that it is initially treated

with a Q-switch laser followed by RA-HQ therapy for

post-laser hyperpigmentation. Melasma sometimes requires

two or three sessions of the RA-HA therapy. Category

IV to VI lesions require combination protocols using

QSR laser and RA-HQ therapy, while Category VII can

be treated with QSR laser treatment alone.

REFERENCES

1. Yoshimura, K, Harii, K, Aoyama, T, et al. A new bleaching

protocol for hyperpigmented skin lesions with a high

concentration of all-trans retinoic acid aqueous gel.

Aesthetic Plast Surg 1999;23:285-91.

2. Yoshimura, K, Harii, K, Aoyama, T, et al. T. Experience

with a strong bleaching treatment for skin hyperpigmentation

in Orientals. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:1097-108.

3. Yoshimura K, Harii K, Masuda Y, et al. Usefulness

of a narrow-band reflectance spectrophotometer in evaluating

effects of depigmenting treatment. Aesthet Plast Surg

2001; 25: 129-33.

4. Yoshimura K, Momosawa A, Watanabe A, et al. Cosmetic

color improvement of the nipple-areola complex by optimal

use of tretinoin and hydroquinone. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:1153-7.

5. Momosawa A, Yoshimura K, Uchida G, et al. Combined

therapy using Q-switched ruby laser and bleaching treatment

with tretinoin and hydroquinone for acquired dermal

melanocytosis. Dermatol Surg 2003;29:1001-7.

6. Yoshimura K, Sato K, Aiba-Kojima E, et al. Repeated

treatment protocols for melasma and acquired dermal

melanocytosis. Dermatol Surg 2006;32:365-71.

7. Sato K, Matsumoto D, Iizuka F, et al. A clinical

trial of topical bleaching treatment with nanoscale

tretinoin particles and hydroquinone for hyperpigmented

skin lesions. Dermatol Surg, in press.

8. Momosawa A, Kurita M, Ozaki M, et al. Combined Therapy

Using Q-Switched Ruby Laser and Bleaching Treatment

with Tretinoin and Hydroquinone for Periorbital Skin

Hyperpigmentation in Asians. Plast Reconstr Surg, in

press.

9. Yoshimura K, Tsukamoto K, Okazaki M, et al. Effects

of all-trans retinoic acid on melanogenesis in pigmented

skin equivalents and monolayer culture of melanocytes.

J Dermatol Sci 2001;27:S68-75.

10. Ortonne JP. Pigmentary changes of the ageing skin.

Br J Dermatol 1990;122:21-8.

11. Bastiaens M, Hoefnagel J, Westendorp R, et al. Solar

lentigines are strongly related to sun exposure in contrast

to ephelides. Pigment Cell Res 2004;17:225-9.

12. Teraki Y, Nishikawa T. Skin diseases described in

Japan 2004. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2005;3:9-25.

13. Cohen HJ, Minkin W, Frank SB. Nevus spilus. Arch

Dermatol 1970;102:433-7.

14. Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, et al. Melasma: a

clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence

study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;4:698-710.

15. Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, et al. Melasma: histopathological

characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol

2002;146:228-37.

16. Mishima Y, Rudner E. Erythromelanosis follicularis

faciei et colli. Dermatologica 1966;132:269-87.

17. Kim MG, Hong SJ, Son SJ, et al. Quantitative histopathologic

findings of erythromelanosis follicularis faciei et

colli. J Cutan Pathol 2001;28:160-4.

18. Daelos ZD. Discussion for Yoshimura K, Momosawa

A, Watanabe A, et al. Cosmetic color improvement of

the nipple-areola complex by optimal use of tretinoin

and hydroquinone. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:1158.

19. Montagna W, Hu F, Carlisle K. A reinvestigation

of solar lentigines. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:1151-4.

20. Ohkuma M. Presence of melanophages in the normal

Japanese skin. Am J Dermatopathol 1991;13:32-7.

21. Nagao S, Iijima S. Light and electron microscopic

study of Riehl's melanosis. Possible mode of its pigmentary

incontinence. J Cutan Pathol 1974;1:165-75.

22. Masu S, Seiji M. Pigmentary incontinence in fixed

drug eruptions. Histologic and electron microscopic

findings. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983;8:525-32.

23. Serrano G, Pujol C, Cuadra J, et al. Riehl's melanosis:

pigmented contact dermatitis caused by fragrances. J

Am Acad Dermatol 1989;21:1057-60.

24. Siragusa M, Ferri R, Cavallari V, Schepis C. Friction

melanosis, friction amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis,

towel melanosis: many names for the same clinical entity.

Eur J Dermatol 2001;11:545-8.

25. Manabe T, Inagaki Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Ripple pigmentation

of the neck in atopic dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol

1987;9:301-7.

26. Colver GB, Mortimer PS, Millard PR, et al. The 'dirty

neck'--a reticulate pigmentation in atopics. Clin Exp

Dermatol 1987;12:1-4.

27. Hori Y, Kawashima M, Oohara K, Kukita A. Acquired,

bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. J Am Acad Dermatol

1984;10:961-4.

28. Hirayama T, Suzuki T. A new classification of Ota's

nevus based on histopathological features. Dermatologica

1991;183:169-72

29. Burkhart CG, Gohara A. Dermal melanocyte hamartoma.

A distinctive new form of dermal melanocytosis. Arch

Dermatol 1981;117:102-4.

30 Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota

with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1745-50.

31. Chan HH, Alam M, Kono T, Dover JS. Clinical application

of lasers in Asians. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:556-63.

32. Lowe NJ, Wieder JM, Shorr N, et al. Infraorbital

pigmented skin. Preliminary observations of laser therapy.

Dermatol Surg 1995;21:767-70.

33. Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P. Q-switched Nd:YAG laser

treatment for acquired bilateral nevus of ota-like maculae:

a long-term follow-up. Lasers Surg Med 2000;26:376-9.

34. Polnikorn N, Tanrattanakorn S, Goldberg DJ. Treatment

of Hori's nevus with the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol

Surg 2000;26:477-80.

|